Spanning computer science, mechanical engineering, biological engineering, neuroscience, and other disciplines, presenters at MIT’s Aging Brain Initiative Symposium Oct. 23 delivered a rich and diverse sampling of the university’s research to address a major global problem: neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

“We still don’t completely understand the mechanism underlying the process of aging. We do know that aging is associated with many health problems, particularly the chronic and progressive diseases of the brain known as neurodegenerative diseases,” said Picower Professor Li-Huei Tsai, founding director of the Aging Brain Initiative (ABI) and director of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. “So at MIT we have sought to encourage new thinking for the aging brain.”

Her remarks introduced the half-day symposium and poster session “Cutting Edge Approaches to Studying the Aging Brain” where hundreds of people gathered at Building 46 and online from 21 countries.

In 2015 Tsai and eight colleagues founded the ABI to engage scientists, engineers, and scholars across MIT to tackle the complex and multifaceted problems arising from age-related neurodegenerative diseases. In 2022 the ABI awarded seed grants to MIT faculty members to help them launch novel projects. Four of those professors provided updates on their work at the symposium, which also featured a keynote from University of Rochester professor Maiken Nedergaard, a pioneering neuroscientist who discovered the brain’s intrinsic “plumbing,” the “glymphatic system.”

The system, which parallels the brain’s vasculature, washes cerebrospinal fluid through brain tissue, delivering nutrients and oxygen that cells need and carrying away waste. Since Nedergaard’s discovery in 2012, her and other labs have shown that the system is deeply relevant to brain health, including age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Glymphatic flow maintains healthy brain functions such as learning, and removes problematic proteins that are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (e.g. amyloid beta, hyperphosphorylated tau, and alpha synuclein). But the system starts to falter as people get older. Moreover, it is active during sleep, but patients with some neurodegenerative disorders sleep poorly, further reducing protein clearance.

“It’s clear that the brain has a major problem with waste clearance, because the diseases of aging, the neurodegenerative diseases, can all be regarded as diseases of a dirty brain,” Nedergaard said.

Nedergaard’s lab continues to characterize the glymphatic system and its role in brain health, including in how problems with fluid efflux from the system may contribute to brain swelling after traumatic brain injury (TBI). She noted that by old age, about half of people will have experienced at least one TBI.

Projects in progress

The complexity of neurodegenerative diseases, however, stems from myriad, multifaceted breakdowns with often-unknown root causes. Several MIT speakers described new work funded by ABI seed grants to understand the mechanisms that drive the progression of those pathologies.

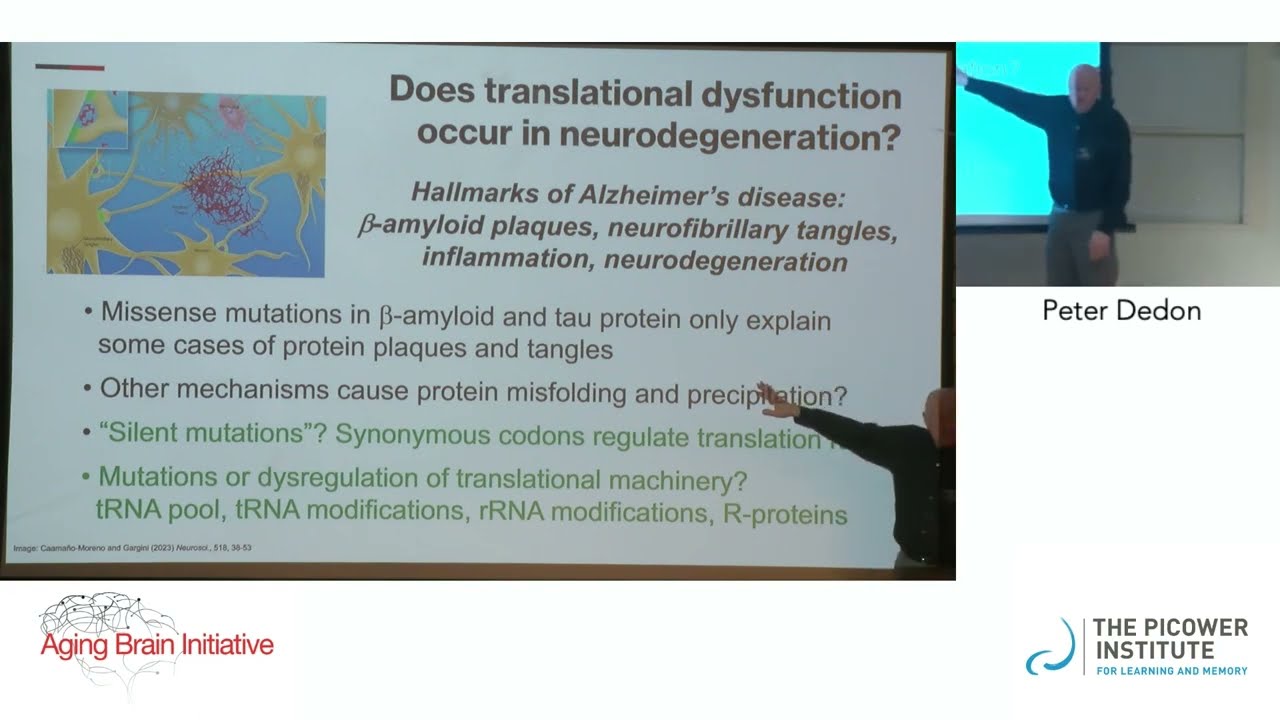

Biochemist Peter Dedon, the Singapore Professor in the Department of Biological Engineering, offered the hypothesis that the pathology of amyloid plaques and tau protein fibrillary tangles in neurodegenerative diseases involves dysregulation of translating messenger RNA into proteins in neurons. Based on their discoveries in cancer and infectious disease, his research team is investigating how aberrant modifications of transfer RNA (tRNA) and silent mutations of codons, which are critical players in regulating the protein translation process, can cause excessive protein synthesis and protein precipitation. Using a mouse model known to produce unhealthy forms of the tau protein, Dedon’s lab is investigating tRNA reprogramming and codon-biased translation of mRNAs in brain tissue, seeking to determine whether these might explain why tau pathology increases sharply as mouse models reach an age threshold.

In her ABI-funded project, d’Arbeloff Career Development Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering Ritu Raman is investigating mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases that impact mobility, such as ALS. Raman’s lab recently developed a tissue culture platform that simulates the mechanical effects of exercise at the cellular level and is developing co-cultures of muscles and neurons. Raman’s hypothesis is that while traditionally people consider the loss of motor function in ALS to be due to problems originating in the neurons, there may also be a benefit in understanding how communication from muscle affects neural growth, or retraction. In another recent study, for instance, she and colleagues showed that repeatedly inducing contraction in engineered muscle impacted cell signaling pathways related to nerve growth, making them more effective grafts in animal models.

Zooming out to the level of brain cells, circuits, and behavior, Institute Professor Ann Graybiel described her lab’s investigation of problems in a brain region called the striatum. She gave an example of work on Huntington’s disease, a neurodegenerative disease of aging. With Picower Institute investigator Myriam Heiman and Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab member Manolis Kellis, Graybiel and research scientist Ayano Matsushima showed how gene vulnerabilities appear to undermine both movement and mood in the condition. In the Graybiel Lab’s new work, they are focusing on what she said is a third “M” that declines with age: motivation, or what we are familiar with as an engaged sense of “get up and go.” Graybiel described how the research is homing in on the brain circuits likely responsible for this disturbing effect of aging, including controllers of the neuromodulator dopamine and non-neuronal companion cells called astrocytes.

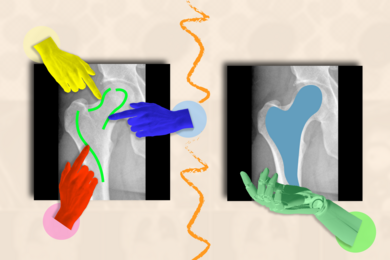

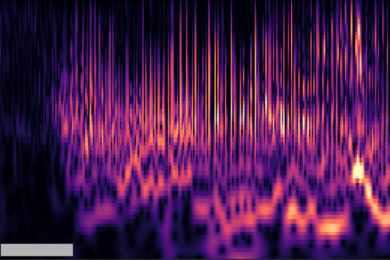

Improving care for people with brain aging diseases requires more than just improvements in understanding pathology and physiology. In his ABI-seeded work, electrical engineering and computer science associate professor Thomas Heldt, a member of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES), teamed up with fellow EECS faculty professors Vivienne Sze and Charles Sodini to develop algorithms and software as powerful but unobtrusive ways to monitor patients’ neurocognitive state. Building on studies showing that eye responses exhibit changes in speed and accuracy amid aging and cognitive decline, Heldt’s lab is building a system that enables sophisticated eye tracking measures on common consumer devices such as iPads. These kinds of measures are often taken under carefully controlled lighting and motion conditions in a lab or clinical environment, but that severely limits opportunities for data collection. In their system, volunteers can use an app that asks them to simply glance to one side or another given a cue and measure their reaction time. The software is able to factor out different lighting or motion artifacts that would confound the measurements.

Plethora of posters

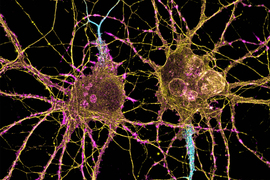

After the talks, in-person attendees spilled out of Building 46’s Singleton Auditorium into an atrium with 26 posters representing 15 MIT and affiliated labs. Postdocs and graduate students described research on topics ranging from brain imaging technologies and methods to studies of cell gene expression, epigenomics, proteomics or metabolomics in neurodegenerative diseases to potential therapeutics, such as gene therapies or sensory stimulation of key brain rhythms.

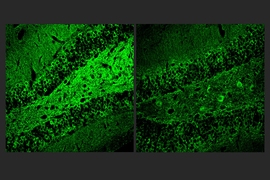

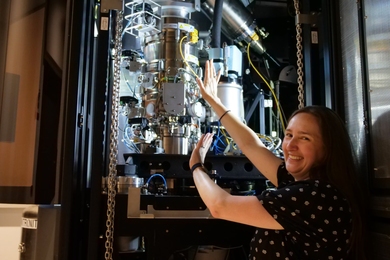

For example, the lab of chemical engineering associate professor Kwanghun Chung of the Picower Institute and IMES displayed three posters describing technologies for processing and imaging whole human brain samples, for instance to analyze Alzheimer’s pathology in postmortem brains. Five members of biological engineering professor Ernest Fraenkel’s lab presented posters describing methods and models for analyzing the “multi-omics” of diseases including ALS, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s.

From the podium to the posters, the afternoon served to showcase the wide-ranging interest across MIT in research to better understand and address diseases of the aging brain.