On Nov. 21, 2019, the sun had set just a couple of hours before on an unseasonably warm day, and Jacqueline Thomas PhD ’20 found herself sitting on the edge of her seat in a typical meeting room in the William J. Hughes Technical Center, part of the Federal Aviation Administration, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Thomas, a graduate student in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro) at MIT, focused intently in front of a small monitor, her eyes fixed on the black screen illuminated by a white outline of the U.S. East Coast and the small, neon green dot that showed the Boeing 777 commercial airplane, which had flown nearly nine hours from Frankfurt, Germany, and was just about to land at Atlantic City International Airport. The last three minutes of this flight were crucial, and it was exactly the moment Thomas had been waiting for.

Accompanied by her advisor, R. John Hansman, professor of aeronautics and director of the MIT International Center for Air Transportation, Thomas felt her heart pounding as she monitored the data the plane generated as it landed in real time, which she checked simultaneously against her predicted outcomes based on her computational model. These final moments of this particular aircraft’s journey would determine if the model that formed a significant portion of her graduate thesis worked in the real world. And it did.

“We waited all day for these final three minutes, and as we watched the plane land through the monitor, my advisor John kept asking if the plane was doing what I expected it to, and it was! Even though I predicted it, it was still surprising,” says Thomas. “I knew the science was sound, I knew the math was sound, but even when everything is going as planned and you are actually seeing it happening with your own eyes, it’s still surreal.”

Just a few short months earlier, Thomas proposed her idea for a “delayed deceleration approach” to Boeing under their ecoDemonstrator (ecoD) program. Essentially, the Boeing ecoD acts as a “bench-to-bedside” innovation accelerator, inviting researchers to pitch novel concepts to improve aviation safety and efficiency that solve real-world challenges for aviation and the environment, where they are tested in real aircraft to demonstrate feasibility. Thomas’ proposal outlined a new flight procedure for pilots to follow while landing that improves aircraft performance around two major challenges the airline is currently facing: carbon emissions and noise pollution.

According to a report released in October 2019 by the Environmental Protection Agency, air travel currently accounts for nearly 2.5 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions, and it is increasing at a much faster rate than initially anticipated. In addition to the negative environmental impact, the increase in the number of commercial flights has increased the number of noise complaints from citizens who live along flight trajectories beyond the jurisdiction of noise regulations, which are typically localized to the areas immediately surrounding airports. The pressure is on for airline companies to work quickly to address these issues, and Thomas proposed a concept that decreased the noise and emissions of existing aircraft without having to modify the aircraft itself, which could be a cost-effective way for airlines to mitigate these issues.

“As soon as a plane is built, it’s hard to change its function. It will generate noise no matter what state it’s in,” says Thomas. “I chose to approach the problem like an integrated system — if you can change the input, you can change the output. In other words, if you can’t change the aircraft itself (the function), you can change how it’s flown (the inputs).”

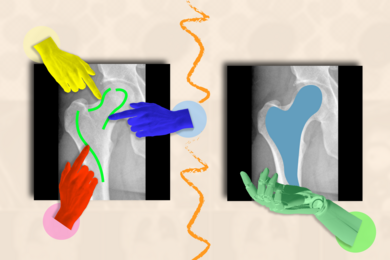

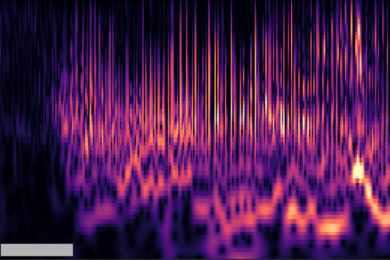

Using this idea, Thomas built a computational framework to analyze aircraft noise and measure the impact of making changes to the operational flight procedure. For her analysis, the inputs included how all of the aircraft components move and interact to generate noise, as well as flight performance data, which accounts for how the aircraft generates noise at different points as it moves through its environment, such as when it accelerates or slows down. The output from this framework was a full-scope overflight noise model, which was then analyzed against community data to paint a clear picture of how making tweaks to the inputs would impact the noise pollution in surrounding communities.

“What resulted from this framework was my concept for the delayed deceleration approach, a new flight procedure where the aircraft remains cleanly configured for as long as possible during approach, meaning the flaps, slats, and landing gear remain upright for as long as possible,” says Thomas. “When the aircraft has a clean configuration, it is more aerodynamic, creating less drag and allowing it to maintain engines at a lower power setting for longer duration in the flight. As a result, the plane burns less fuel, decreasing carbon emissions, and generates less noise for the community on the ground.”

Under the ecoD program, Thomas handed her procedure over to Boeing engineers in Seattle, Washington, who communicated it to the crew throughout the flight via a chat feed that Thomas and Hansman could see on the monitor, along with the plane’s location. Immediately following the landing, the all-women flight crew joined Thomas, Hansman, and the group of Boeing engineers and administrators from the ecoD program for a debrief.

“The pilots reported they felt very comfortable with the procedure, and didn’t experience any flyability issues. When the models say that it works and has all of these benefits, and the pilots say ‘yes, we can fly this,’ and a commercial plane actually flies the procedure and matches the predictions from the models, then it really shows that we can do this, and we should because it’s a win-win for everyone,” says Thomas. “My goal for the future is to make this a standard flight procedure, which means I need to keep working on refining this process so we can scale it up in a way that makes sense to implement in real airlines operating today.”

After nearly six years and countless hours spent at the computer in the lab, this was an extraordinary opportunity for a graduate student; it can take years to put together a flight test, and thanks to the Boeing ecoD program, this test came together in a matter of a few months. It was the perfect way to begin winding down her final year at MIT.

With the excitement of the ecoDemonstrator behind her, Thomas set her sights on preparing for one of the biggest milestones in a graduate student’s career: the thesis defense. Typically, this rite of passage is a celebratory one that comes after months of coordinating busy thesis committee schedules and practicing presentations backward and forward. Thomas was also in the process of job hunting, interviewing for academic positions in between putting the finishing touches on her thesis presentation. And then the coronavirus hit. As the pandemic and MIT’s response to it rapidly unfolded, campus closures, travel restrictions, and stay-at-home orders snapped the public health crisis into focus. Everything became a scramble as Thomas watched months of planning go out the window, and she knew she would have to improvise quickly.

“I had to move my defense online, and my internet at home is really sketchy, so I was terrified,” says Thomas. “It was weird not worrying about the typical things you would normally worry about before a thesis defense, like wondering if my presentation was good enough. I was more nervous about needing to defend my thesis by holding my phone up to my face.”

Thomas submitted a formal request to MIT to use one of the few classrooms that remained open on campus by appointment only to defend her thesis. Instead of defending her thesis to a room full of people, she was in an empty room on a Zoom call, where she could only see five attendees at any given time. When she finished her presentation and answered all of the questions from her thesis committee, she was asked to log off of the Zoom call, where she sat in silence in the cavernous room, alone. Five minutes later, she received a congratulatory phone call, and just like that, she was a doctor.

“It was bizarre. Normally you are with other people to talk to and celebrate with, but I was just in a room by myself, and there was no one else at MIT,” says Thomas. “One of the cool things about holding my defense virtually was that my friend in Japan logged in to watch, even though it was 2 a.m. his time. But my fiancé, who is also studying aerospace as a grad student at Georgia Tech, wanted to come be with me for my defense, but we decided together that with the safety measures asking visitors from out-of-state to self-quarantine, it just wasn’t possible.”

Thomas, like many graduate students, lived in an off-campus apartment with a roommate, a postdoc at a neighboring university, who had only recently moved in. Since graduate students and postdocs spend so much time on campus, this is a typical living arrangement. Many graduate students attend school far from home, so the stay-at-home order can be particularly isolating, especially when you are living with a near-perfect stranger without work to focus on.

Since turning in her thesis, Thomas kept busy with early-morning runs around the Charles River, refreshing her Japanese and Spanish-speaking vocabulary, catching up on TV shows she'd fallen behind on while dealing with the demands of graduate school, and trying to maintain glimmers of normalcy, such as attending regular church services (albeit virtually). While exciting career opportunities are on the horizon, many other personal plans, like her wedding date, are at a standstill as we remain in the grip of uncertainty at the mercy of a global pandemic.

“It feels like I’m in a limbo state, because my work is pretty much done and I’m just waiting for the next chapter to start, which feels like it’s taking longer than usual because so much of it is spent alone,” says Thomas.

For Thomas, one of the more difficult aspects she is grappling with is the abrupt ending of her time at MIT. As a first-generation college student, Thomas’ family had set aside money for the major expense of traveling to experience MIT Commencement with her, and it was tough to watch her families’ travel plans, and the hard-earned money put toward them, evaporate.

“Grad school is hard, but looking back, you realize how much you grew throughout the experience, and I wanted to tip my hat to MIT when I left,” says Thomas. “This is my sixth year here, and it’s a long time to be involved at a place and then suddenly, it leaves you within three days. I think the hardest thing for me has been this lack of closure. It’s like a severed connection.”

Thomas is hopeful for the future. She will become a member of the faculty at her alma mater, the University of California at Irvine, where she will teach and continue her work on aircraft noise mitigation and pursue exciting new directions studying electric aircraft. She also hopes for future events that could bring the Class of 2020 back on campus to say a proper goodbye — once it is safe to do so.