At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, when many hospitals ran out of beds and ventilators, the fingertip pulse oximeter — a $20 neighborhood drugstore purchase — became a primary arbiter of whether a patient was “sick enough” to gain admission to an emergency room.

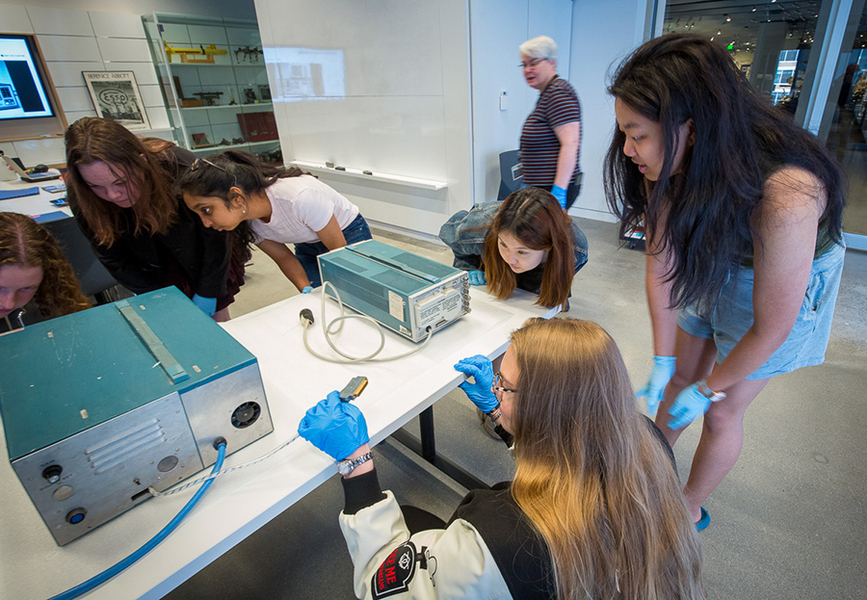

This spring, surrounded by antique telescope models in a classroom tucked inside the MIT Museum, 10 students bent over a square-shaped seminar table. They were building basic pulse oximeters from low-cost do-it-yourself (DIY) kits of assorted wirelings from TinyCircuits.

This was just one meeting from MIT class 21A.311 (The Social Lives of Medical Objects), a course taught by Amy Moran-Thomas, associate professor of anthropology and the 2022 winner of the Edgerton Faculty Achievement Award.

Moran-Thomas observed that anthropology’s key frameworks for studying material culture were often missing from spaces of device design and pre-med coursework. She developed the class in 2019 to encourage students to learn from ethnographic approaches, the MIT Program in Science, Technology and Society, and history to explore social inquiries related to health objects.

Zeroing in on a case study concerning a different health material, device, or technology, each session probes what Moran-Thomas refers to as “the social assumptions that get built into objects meant to improve health.”

For the week’s focus on “Politics of Measurement,” students rolled up their sleeves for the lab portion of class, joined by Jose Gomez-Marquez of MakerHealth. He guided the teams through assembling their own oximeter.

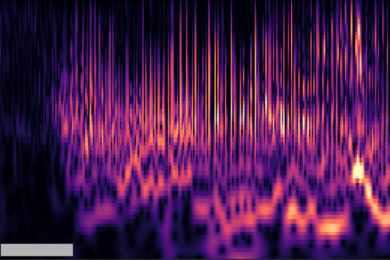

Then the students were encouraged to interact with it alongside two prepackaged models that displayed readings from sealed-off “black boxes.” The open-design TinyCircuits models demystified these inner workings, which Moran-Thomas pointed out is a reminder of all the choices that any black box can contain. Students attached the DIY sensors to a microcontroller board, and played with lines of code as they wondered how small edits might impact the readings of sensors held to their fingertips.

Nicole Seman '23, a recent graduate in mechanical engineering, has Type 1 diabetes and uses an insulin pump. She enrolled in the course because being dependent on a medical device is something she knows all too well. In a paper, she wrote about the experience of switching pumps, drawing on an ethnography about what assumptions of “normal” bodies get encoded in global cochlear implants and their sensory futures.

After tinkering with the DIY oximeter, Seman noted how some students immediately reported wide discrepancies when wearing two prepackaged devices at once. “It’s a diverse class, and so we were able to see firsthand how the pulse ox works differently depending on skin tone.”

A class with timely implications

This observation, perhaps obvious in 2023, received tremendous pushback when Moran-Thomas first published a widely read essay in the Boston Review laying out the evidence for how pulse oximeters can offer biased results for people with darker skin.

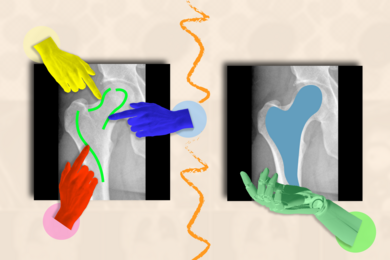

In the essay, she explained that oximeters gauge oxygen levels in part by measuring color absorption: blood’s iron-containing hemoglobin is brighter crimson-colored when fully saturated with oxygen, and a cooler purple-red when holding less oxygen. To measure this, a pulse oximeter shines two light wavelengths through the skin — but many device developers had not carefully accounted for the ways light is absorbed differently across various skin tones, often designing and testing it with largely white test groups. Distorted measurements can be amplified by algorithms, and Moran-Thomas warned that consequences of this inherent bias could produce device errors with life-altering implications, such as whether a patient is admitted to the hospital or offered oxygen.

In Moran-Thomas’s classroom, students had the opportunity to open up devices and see for themselves the human choices that “black boxes” can encode. It was an elegantly simple example of how easy it is to assume that numbers are neutral in health care — when, in fact, codes and the way they are interpreted are often rife with subtle bias.

She says, “Something I hoped the students would see from this exercise is that many things that are taken to be raw data are actually processed signals, mediated by design decisions and unequal histories. Social assumptions get materialized in how we build technology and make measures.” Those assumptions about who a device’s end users will be directly impacts whether the design and its function are equitable — or dangerously unequal.

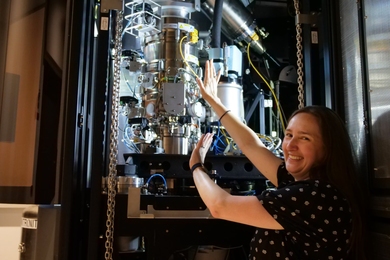

The session ended that day with a visit from Tufts University associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and MIT alumna and recent MLK Visiting Professor Valencia Joyner Koomson ’98, MNG ’99. Working in a professional landscape where only 2 percent of engineers are Black women, Koomson presented her work to build a “smart” pulse oximeter that works for everyone, with an eye toward global accessibility.

Moran-Thomas says that Koomson’s presentation showed why equitable design is important, and conveyed to students how such work means much more than just diverse testing: it also takes diversity in engineering and among experts.

Device tours

For one of the field trips early in the semester, Moran-Thomas arranged a “devices tour” of an MIT ambulance led by junior Abbie Schipper, who volunteers at MIT Emergency Medical Services as an emergency medical technician. Schipper took students through the vitals equipment, including blood pressure monitors and cuffs, and pulse oximeters.

Schipper’s tour also highlighted how wider consciousness of device questions is growing in the medical community. Already well-aware that pulse oximeters do not work equally for everyone, she brought additional examples to the students’ attention: Blood pressure cuffs, which work manually, are notoriously unreliable as the ambulance accelerates down potholed Cambridge roads. “You treat the patient, not the number,” Schipper told the students. “The ambulance itself is a big medical device.”

Students in the class appreciated hearing how Schipper’s own experiences working in emergency transport impacted her thinking about design questions as a mechanical engineering student.

Chloe McCreery, a senior planning to attend medical school, says “This class has really made me think; we all have a responsibility to make sure these devices are created and used ethically.”

Drawing future lessons from historical objects at the MIT Museum

The class also pulled from the Technology Collection at the MIT Museum. At one recent session, students examined one of the museum’s most recent acquisitions, a retro detector known as the Bedside Arrhythmia Monitor. It was rediscovered by someone cleaning out an old building on campus and made its way back to the museum last fall.

“The MIT Museum started to research it, and realized it was a milestone device,” Moran-Thomas says. “They invited our class to contribute to exploring the social side of the story.” Museum curators had been able to ascertain that the rectangular device was prototyped in MIT’s Biomedical Engineering Center for Clinical Instrumentation in the 1970s, and bore metal tags from years it spent in service at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and NASA.

The Bedside Arrhythmia Monitor helped lead to the creation of PhysioNet, today one of the most widely used open health databases in the world. Moran-Thomas tracked down Paul Scott Schluter, who developed the detector for his thesis, and his advisor, MIT Professor Roger Mark. They spoke with the class virtually to share recollections of how the arrhythmia detector and its pivotal open database came into being. During their chat, the device sat on a table between the generations, and a conversation began about its potential implications for the next chapters of open data design in health.

“Each case study is meant to emphasize one of anthropology’s core lessons: At every stage of an object’s creation and use, there are people with histories and insights to consider,” Moran-Thomas says.

Now, it’s up to her students to bring ethnographic questions and social approaches into their future work.