While people turn to digital media for news at high rates, algorithms for manipulating media continue to grow more powerful. In a Pew Research Center survey (August/September 2020), 53 percent of adults in the United States say they get news from social media “often” or “sometimes.” People have long been aware of phenomena such as “doctored” photos and misinformation at large, but machine learning is enabling the proliferation of “deepfakes,” videos or images of fake events with increasing sophistication.

Now, the MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality (MIT Virtuality for short) has created a course that addresses misinformation both in terms of specific contemporary technological phenomena and a broader media perspective.

“We are currently experiencing an information crisis,” says Joshua Glick, education producer for this MIT Virtuality project and an assistant professor of media studies at Hendrix College. “A combination of political, technological, and economic forces has propelled the spread of misinformation and disinformation throughout our media environment — and the crisis has only been amplified by the pandemic.”

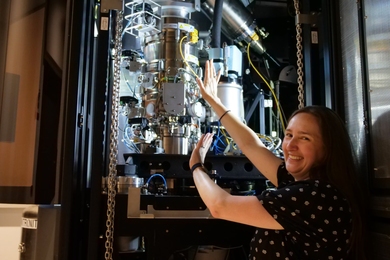

The MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality, part of MIT Open Learning and directed by Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory professor D. Fox Harrell, has created a free online course, Media Literacy in the Age of Deepfakes, with the goal of giving educators and independent learners the resources and critical skills to understand the threat of misinformation. In addition to teaching participants how to decipher fact-based assertions from lies and credible sources from hoaxes, the course aims to place deepfakes within a larger history of media manipulation and to show how activists, artists, technologists, and filmmakers are using AI-enabled media for a wide range of civic projects.

The course is implemented as a dynamic, multi-layered website including video and case study materials, as well as offering much more context and information through different self-paced learning modules. An illustrative example used in the course is “In Event of Moon Disaster,” an Emmy-winning MIT Virtuality production co-directed by Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund. The project showcases a deepfake of President Nixon delivering the real contingency speech written in 1969 for a scenario in which the Apollo 11 crew was unable to return from the moon, and features numerous learning and analysis resources.

The Media Literacy in the Age of Deepfakes project was supported by a grant in higher education innovation from the Abdul Latif Jameel World Education Lab (J-WEL) to design both a series of in-class educational experiences for students and an online course to serve more broadly as a resource for educational institutions. Glick, an expert in the public humanities, was hired to work on the project by Professor Harrell, the grant’s principal investigator. Other contributors to the project include Senior Project Manager Rita Sahu and Digital Publication Specialist Cathleen Nalezyty at OpenCourseWare, as well as web developer Nicolae Herrera, consulting designer Ksenia Slavina, and graphic artist Dan Sharkey, to create a rich learning experience suitable for higher education.

“The course responds to an increasing need to address misinformation and disinformation on a variety of fronts ranging from policy to technological interventions — in this case we are focused on enhancing public knowledge and understanding,” says Harrell. “Deepfakes are just one example of a technology of virtuality, which we describe as technologies that blend the imagination with the physical world. Our center pioneers creative and impactful uses of such technologies for the learning and the social good — and to combat their uses toward negative ends such as disinformation. The goals with this course are to empower students and educators to be critically aware of their media environment, and to help equip them to become discerning interpreters of the media they encounter daily.”

The course was designed with maximum flexibility in mind, comprising three individual learning modules that can be taught individually as “micro-units” within a media studies, computer science, or communications class, or all together as an extended one- to three-week section.

In addition, the course website includes a comprehensive section of resources with assignments related to the modules. For example, there is a StoryMaps project that incorporates research in historical newspapers and a design prompt to prototype a new work of synthetic media. There are also a long-form bibliography and a sample syllabus that can be used for a semester-long class. The course team included many citations and references throughout the modules, allowing educators to dig deeper into the subject matter and learn more about specific topics, such as 20th-century disinformation or AI-enabled art.

Media Literacy in the Age of Deepfakes has been used at Dartmouth College and other universities as well as at MIT, in courses in Comparative Media Studies and Media Arts and Sciences. It is also hosted through MIT OpenCourseWare, making it available to the millions of learners and educators around the world who turn to that website for the best of open access learning materials from MIT.

“It has been eye-opening and rewarding to hear from colleagues about how their classes have been engaging with this online course,” says Glick. “If students can be a bit more critical about the articles, videos, and images that pop up on their social media feeds, the project will have done some good. Hopefully, they can apply what they are learning to their coursework and to their professional and public lives beyond the university.”